Post European History

The Tarkine features a unique and fascinating pioneering heritage. The area was one of Tasmania’s most elusive and daunting regions for early explorers and pioneers.

Evidence of Tasmania’s pioneering history exists in and around the Tarkine in the form of such icons as the historical settlements of Temma, Corinna, Balfour, Waratah, Luina and Magnet; incredible bush architecture such as the remains of the old Hilders River Bridge Crossing; the old Emu Bay Railway which runs down the eastern fringes of the Tarkine; Huon Pine Gravestones near Corinna; and the stories of the early explorers such as Henry Hellyer, Jorgen Jorgenson and others – that make fascinating interpretation of the Tarkine region for tourists.

Exploration

Probably the earliest European visitors to the Tarkine region were ‘piners’ who navigated many of the coastal rivers including the Pieman River, collecting cargoes of Huon Pine from 1816 onwards. Beyond these earliest of visitors, there were three main ‘waves’ of land exploration of north-western Tasmania and the Tarkine region (as identified by C.J.Binks 1989). The first was in the form of searches commissioned by the Van Diemen’s Land Company looking for land to settle and graze, the second the rush for gold, and the third the rush for copper and other minerals.

The VDL Company was officially formed in 1825 by the Colonial Office and was ordered to settle an area that was described as “beyond the ramparts of the unknown” (Murray 1988:101)”. The government of the day allowed land to be granted to the VDL Company in north-west Tasmania. The VDL’s Surrey Hills Block, now owned by Gunns Ltd, borders the eastern fringes of the Tarkine region. Employees of the VDL Company blazed tracks through some incredibly dense and difficult country in and around the Tarkine, with the VDL company’s chief surveyor being Henry Hellyer – of whom the Hellyer river takes its name. Other surveyors, Lorymer and Jorgenson, were organised by the VDL company in 1827 to map the west coast down to the Pieman River. Along the way, they detoured from Sandy Cape, eastwards to Mt Sunday, and as far as the Longback, before doubling back and continuing down the coast. Having crossed the Donaldson River with great difficulty, they were forced to spend the night in thick forest on the eastern bank.

“Fallen trees in every direction had interrupted our march, and it is a question whether ever human beings either civilized or savage had ever visited this savage looking country. Be this as it may, all about us appeared well calculated to arrest the progress of the traveller, sternly forbidding man to traverse those places which nature had selected for it’s own silent and awful repose.” – Jorgen Jorgenson, 1827 (as quoted in Binks 1980:75)

Pastoral Expansion

By the 1830s, a number of squatters were inhabiting parts of the Tarkine coastline and using the region for cattle grazing. Temma, or ‘Whales Head Boat Harbour’ was one of the best landing places on the Tarkine’s coastal region, though still very dangerous in rough seas. A number of boats were wrecked trying to navigate along the Tarkine coast, including trying to navigate in though the mouth of the Pieman river.

By 1892 there was a mining boom in Zeehan, leading to the driving of cattle down the Tarkine coast occasionally, where they were swum across the mouth of the Pieman river, to be sold on the south side of the river to supply meat to the town of Zeehan. Since the early 1890s, some sections of the Tarkine coast south of Marrawah have been seasonally grazed by cattle.

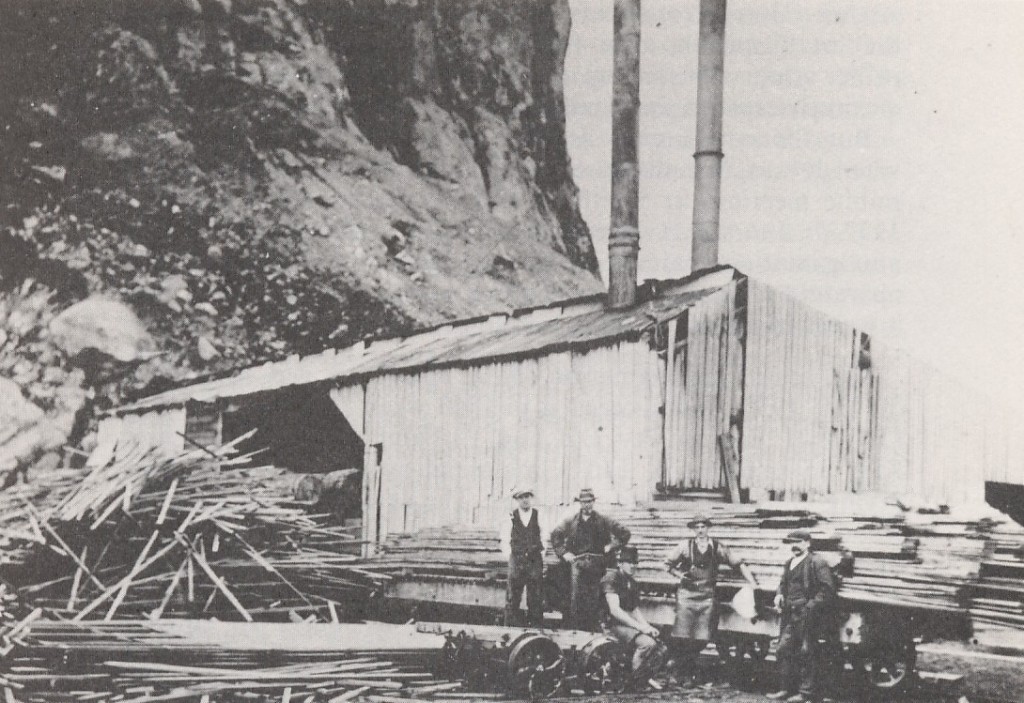

Logging

When Europeans first arrived to Tasmania, dense rainforests covered much of north-west Tasmania. What seemed like an unending sea of forest was looked at as a hindrance to progress, and the development of the colony. While ringbarking was initially used to clear forest, as the colony grew, logging for timber became an increasing activity. Ex-convicts from Launceston, employed as bark strippers, undertook the first logging activities in the north-west of Tasmania well away from the Tarkine – working in the Port Sorell area in the 1820s and 1830s.

However, as the Victorian Gold Rush hit its straps in the 1850s, demand for timber grew – and the rate of timber cutting in Tasmania rapidly increased, with the North-West a focal region, due its proximity to harbours and mainland markets. It was during this boom that mechanised sawmilling technology was introduced, increasing the rate at which millers were able to mill their cut. By the 1860s, cutting of rainforest timbers also became a focus, especially Blackwood, focussed as an export to Melbourne for furniture production. Timber cutting in circular head was established in the 1880s, when a mill was established at Smithton to exploit the stands of virgin swamp blackwood, which previously had been ringbarked and burnt by agricultural settlers intent on establishing pasture land. The success of the first sawmill, encouraged other farmers to take up timber felling. However, this led to concerns at overcutting, as far back as 1886, by the Conservator of forests;

“If blackwood is destined to continue to be a staple product of the North-West Coast, it is quite evident that unless means be taken to propagate and conserve it, also to prevent the wanton cutting of trees necessary for seed, and to foster the indigenous growth, this tree must in the nature of things become scarce, and blackwoods an article of commerce practically extinct, that is to say, on the Coast lands in proximity to good roads, ports or shipping places.” (Paper of parliament, July, 1886)

Overcutting, and the great depression, led to a series of mergers of small family owned sawmills across North-West Tasmania during the 1940’s, with over-saturated markets forcing rationalisations of the timber industry in Circular Head and the North-West between 1940 and the 1970s, with the rights to logging subsequently becoming vested in a smaller number of bigger companies. The introduction of wood-chipping operations into the logging industry in Tasmania further drove rationalisations within the industry. Wood-chipping is now the key focus of logging operations in North-West Tasmania, with woodchips representing more than 80% of the timber cut from public forests. The Hampshire woodchip mill, situated south of Burnie, has one of the biggest turnovers of any woodchip mill in the Southern Hemisphere, and employs between 12 and 20 full-time employees. Apart from the Hampshire woodchip mill, there are also sawmills based in Smithton and Somerset, with small specialist furniture makers and craftsmen dotted along the North-West coast as well.

Mining

Mining and mining exploration has been a part of the Tarkine’s past, with historically one of the biggest mines just outside the Tarkine, Mt Bischoff, representing a key part of the mineral boom that occurred in Western Tasmania in the 1800s and early 1900s.

Gold was the first mineral that miners prospected after in the Tarkine region, with a number of prospectors drawn to the coastal region in the 1860s and 1870s but few significant finds resulted.

Interest in other minerals developed, with copper, wolfram and iron being the major interests in the early 20th century. The Balfour mining field was the most active area in the western Tarkine, with the discovery of copper and tin leading to the Balfour boom between 1902 and 1912. The town briefly boomed with a population of up to 700, and a tramline having been built from Balfour to Temma in order to ship the ore. Many other mineral leases were taken up at around this time, with the tributaries of the Pieman River attracting gold prospecting from the late 1800’s.

The remoteness and ruggedness of the Tarkine and the west coast of Tasmania meant that many of these mineral rushes were short-lived. The wildness of the Tarkine often won out over prospectors’ hopes of getting rich. Living in western Tasmania was very tough, and produced a distinct group of people.

Binks (1989) states that: “There was a recognition from the beginning that west coasters were a people apart, who had to fight for whatever they needed in a world which tended very easily to forget their existence. They joined battle with unresponsive governments just as persistently as they battled against an unresponsive country to establish a place for themselves and carve an industry and society out of a wilderness. From this fight they emerged with a strong political and social identity” (Binks 1989:5)

The towns in and around the Tarkine were made up of many permanent residents, while many others were transients, who would move from job to job around mining fields and sawmills in Tasmania. Many of these towns relied on the mines to exist, and so in many cases have been reduced to ghost towns when mining and prospecting ceased. Examples of the early mining activity in the Tarkine region are still apparent in places like the Heazelwood mineral field and Magnet mines area.

The major mine that currently operates within the Tarkine region nowadays, is the Savage River iron ore mine, which was established in 1967.

Shipwrecks

The Tarkine’s coastline is notoriously rough, as it faces the full force of the roaring forties. The offshore waters adjacent to the Tarkine coast were difficult and dangerous for navigation, being subject to strong onshore winds, strewn with offshore reefs and rocks, and with few safe, protected anchorages. Nevertheless, for many years the sea was the principal means of access to this area. As a result many shipwrecks have occurred along the Tarkine coast, including the following vessels: Lady Denison (1850), Rebecca (1853), Alert (1854), Ethel Cuthbert (1877), Flying Arrow (1878), Sarah Anne (1879), Eva (1880), Tasman (1891), Yolla (1898), Australia (1899), Hazard (1908), Koonya (1919), and Kahika (1940).